This week we are taking an academic dive into middle grade sci-fi with a special guest post by friend and fellow VCFA grad, Diane Telgen. I asked her to condense her brilliant thesis into a blog post, a herculean request to say the least. Of course, she did it easily and without complaint.

Please welcome, Diane Telgen.

Diane Telgen is a freelance writer and an editor with Angelella Editorial. She holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts; parts of this essay were excerpted from her critical thesis. Her current works in progress include a middle-grade science-fiction novel involving first contact at a lunar-orbiting space station. You can find her online at dianetelgen.com or on Twitter @originalneglet.

I’ve always had a love for science fiction. My earliest memories include my dad telling me to pay attention to the television because the future was here: man was about to land on the moon. Dad was a tech geek before such a term even existed, and novels by sci-fi’s Big Three—Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, and Robert A. Heinlein—littered his bedside table. Any time Star Trek came on, first-run or repeats, we tuned in. There’s no question I owe my father for my affinity for science fiction and all things space-related.

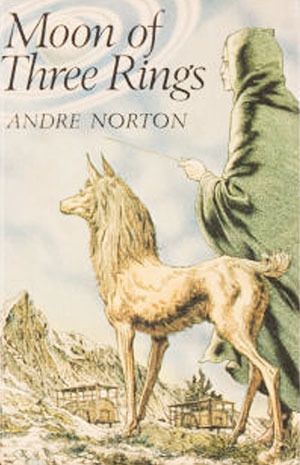

A visit to my school library in sixth grade opened my eyes even further to the possibilities of the genre. I read all kinds of books voraciously, but one day I chanced upon a novel by Andre Norton titled Moon of Three Rings. I browsed the flap copy and thought the story, about a young crewmember on a galactic trading ship, sounded interesting. Then I scanned the first few pages and paused on the title page, where handwriting marred the clean white page. Under the byline, the school’s librarian had penciled in a different name: Norton, Alice Mary.[1]

My young self, barely cognizant of the feminist movement just then transforming the wider world, stared. Wait a minute—you mean GIRLS can write about SPACESHIPS?!?!?!

From that point on, I devoured whatever science fiction I could find. Library books, my dad’s books, books I wheedled my mom to buy whenever we visited the book store … I wanted as much as I could read. By the time I was in my teens, the paucity of YA literature at the time meant I’d moved on to adult sci-fi, and fantasy, too. I was a full-fledged genre nerd, loud and proud.

My sixth-grade self somehow recognized that someday I’d want to write my own novels, and after finishing college I began writing in my spare time. Eventually I realized that my natural narrative voice lay closer to middle-grade and young-adult than adult genre fiction, and both my writing and reading habits turned back to children’s books. Sadly, I wasn’t finding much sci-fi being written for younger readers—or if I did, it wasn’t labeled as such. Star Trek and Star Wars and comic-book movies featuring mutant, scientist, and alien superheroes may have dominated pop culture over the past two generations, but publishers kept calling popular series like The Hunger Games or Divergent “dystopia” instead of the broader genre term: science fiction. Yes, there was Nancy Farmer’s award-winning House of the Scorpion, but that novel about cloning seemed to be an outlier.

When I decided to go to Vermont College of Fine Arts to get my MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults, I wrote on essay on the brilliant ways Farmer made the scientific aspects of her world easily accessible to her young readers. My advisor that semester, David Macinnis Gill—the author of the YA sci-fi series beginning with Black Hole Sun—suggested that maybe I’d found a subject for my critical thesis. Yes! I thought. I read as many middle-grade sci-fi novels as I could, from Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time—a childhood favorite—to more recent works. While the bulk of my thesis analyzed the methods these works used to present science, I opened by examining whether science fiction was an appropriate genre for a younger audience. As you can probably guess, my conclusion was another Yes!

I came to this verdict despite the comparative dearth of middle-grade SF novels and the conventional wisdom, as one critic observed, “that while even very small children can appreciate the marvelous, ... it is difficult to convey scientific marvels to anyone who lacks an adequate grounding in basic science.”[2] Another critic made the fair point that many children’s books are “science fiction only by courtesy. Aliens and robots are reduced to the level of icon and take the place of fairies, elves and monsters.”[3] But she also questioned whether it was even possible to write “full” sci-fi for kids, arguing that works for children often neglects the genre’s essential theme of change in favor of resolutions involving coming-of-age or family issues. In true sci-fi, “the resolution is not the end of the story, it is the beginning, for SF resolutions are about change and consequence.”[4]

This is too narrow a definition, however, especially when considering sci-fi’s origins and development. The term has undergone many revisions since 1926, when pioneering magazine editor Hugo Gernsback defined “scientifiction” in the first issue of Amazing Stories as “a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision.”[5] The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction notes:

[while] there is really no good reason to expect that a workable definition of sf will ever be established, ... we may feel that, if sf ever loses its sense of the fluidity of the future and the excitement of our scientific attempts to understand our Universe—in short, as more conservative fans would put it with enthusiasm though conceptual vagueness, its Sense of Wonder—then it may no longer be worth fighting over.[6]

Portraying possible futures and using science to comprehend the universe seems clear enough, but how does one define the “sense of wonder”? The phrase is open to interpretation, but many critics connect it with the work of Clarke, one of the best-known sci-fi authors of the twentieth century. He argued that “although it has become something of a cliché, perhaps the most important attribute of good science fiction—and the one that uniquely distinguishes it from mainstream fiction—is its ability to evoke the sense of wonder.”[7] In works such as Rendezvous with Rama and 2001: A Space Odyssey, Clarke’s characters—and by extension the reader—marvel wide-eyed at encounters with aliens or alien technology, bringing to their experiences the same “sense of wonder” that a child has when learning about the wider world.

Two other pioneers of SF’s first Golden Age also remarked upon the inherent appeal that the genre holds for young readers. Heinlein, whose early SF novels of the 1950s were marketed to juveniles, asserted that “in a broader sense, all science fiction prepares young people to live and survive in a world of ever-continuing change by teaching them early that the world does change.”[8] The prolific and influential writer Asimov, best known for his “Three Laws of Robotics,” agreed that “the great service of science fiction” was “to accustom the reader to the possibility of change, to have him think along various lines—perhaps very daring lines.”[9]

To anyone who thinks that science fiction isn’t appropriate for the middle-grade audience, or that you can’t write “real” sci-fi for them, I counter: the genre has an inherent appeal for young readers. They explore the world around them with the natural curiosity of a scientist and are more open to learning about the weird and wonderful universe around them. So go build your new and exciting sci-fi worlds. Encourage young minds to remain open, to find joy in exploring a universe full of possibility, and to consider strange new worlds without automatically rejecting them as different. These are worthy goals for a writer in any genre.

[1] Never mind that “Alice Mary” legally changed her name to “Andre” long before the book’s publication; librarians are thorough when it comes to their catalogues.

[2] Levy, Michael M. “Editor’s Introduction II: Boys and Science Fiction.” The Lion and the Unicorn 28.2 (2004): ix-xi.

[3] Mendlesohn, Farah. “Is There Any Such Thing as Children’s Science Fiction?: A Position Piece.” The Lion and the Unicorn 28.2 (2004): 294.

[4] Mendlesohn, p. 289.

[5] Quoted in Stableford, Brian M., John Clute, and Peter Nicholls. “Definitions of SF.” The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Eds. John Clute, David Langford, Peter Nicholls, and Graham Sleight. Gollancz, 2 Apr. 2015. Web.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Clarke, Arthur C. Greetings, Carbon-Based Bipeds!: Collected Essays, 1934-1998. Ed. Ian T. Macauley. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1999, p. 404.

[8] Heinlein, Robert A. “Science Fiction: Its Nature, Faults and Virtues.” Turning Points: Essays on the Art of Science Fiction. Ed. Damon Knight. New York: Harper & Row, 1977, p. 27.

[9] Asimov, Isaac. “Social Science Fiction.” Turning Points: Essays on the Art of Science Fiction. Ed. Damon Knight. New York: Harper & Row, 1977, p. 58.