“As great scientists have said and as all children know, it is above all by the imagination that we achieve perception, and compassion, and hope. ”

When I was younger, science fiction, fantasy and horror formed the bulk of my discretionary media consumption. I lived in a lower-middle class, racially segregated neighborhood in Cleveland, Ohio. Still, I wanted for nothing. I was born in a loving nuclear family. I was within walking distance of my school and two library branches (imagine - two!) To supplement, I regularly took the Rapid Transit and two buses downtown to the massive Cleveland public library where, armed with as many books as I could carry, sat among the stacks and endless card catalogues immersed in other worlds - dreaming. At night I’d eagerly anticipate the next installment of Outer Limits, the irony embedded in Night Gallery, the scares and hi-jinks of the Robinson family expedition in Lost in Space, and finally, devoured Star Trek with its multicultural cast, cheesy paper maché planets and bad alien makeup jobs. Immersed in books and media I dreamed of what I could be and of life, not just outside of my neighborhood, but outside of the planet’s boundaries. It was liberating.

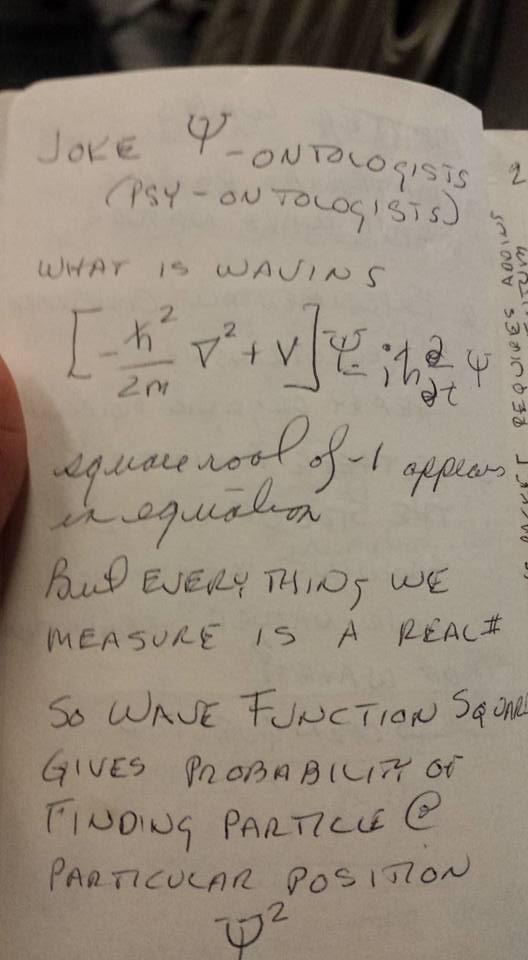

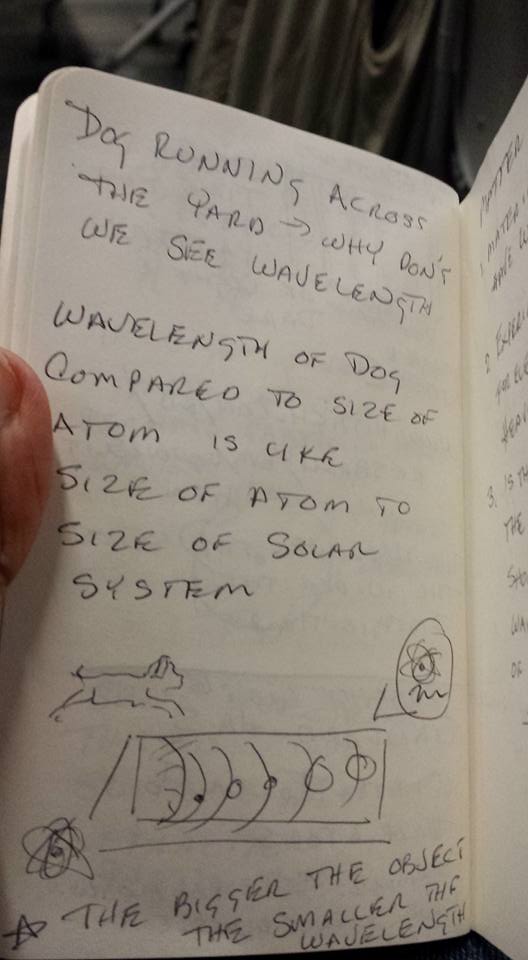

Science fiction was my refuge. It disguised real world conflicts in pages filled with fantastical things that didn’t exist yet outside of the mind of the author. I used my imagination to see the rich landscape of the cylindrical alien ship’s interior in Arthur C. Clarke’s “Rendevous with Rama.” It made sense and didn’t at the same time. As a teenager, I didn’t know enough science to understand the ramifications of creating a city in a zero gravity environment. And who had heard of Quantum Physics? Certainly not me! Decades later I watched Christopher and Jonathan Nolan’s movie “Interstellar” which depicted a similar environment (Cooper Station) and suddenly the images I’d stored from Clarke’s book came into view as well. Aha! - Circular rotations and gyros to simulate gravitational pull in the vacuum of space! And to that end, I had another practical application for my school formulas about radius, diameter and circumference.

“Fantasy is totally wide open; all you really have to do is follow the rules you’ve set. But if you’re writing about science, you have to first learn what you’re writing about. ”

So why is this important - both then and now? It is through science fiction I discovered my love of math and science. In the endless realistic fiction books shoved at me by rigid school curriculum I saw only the human condition as it existed in the past or present. The characters were people I didn’t know or could never be. I didn’t particularly find Tudor Stuart England relevant as a path forward even as I processed that there were “Tudor-style” mansions in the rich neighborhood nearby. I suppose I could have used math to extrapolate Pa’s crop yields in Little House on the Prairie. And, to be honest, I was (and am still) full up on stories of black people who solved a plot construction only to still be stuck in the same dreary reality at the end.

As an alternative, science fiction provided a place for the well-adjusted and the misfits and outcasts to coexist (the latter often the ones executing technological advances in our future). In “A Wrinkle In Time,” a nerdy girl explored multiple dimensions and tesseracts. “Forbidden Planet” introduced Robby the Robot (albeit a man in a robot suit but I was willing to suspend my disbelief). Now scientists have created real robots with artificial intelligence. Space flight? Jules Verne was taking us to the moon long before the United States and Russia designed their first rocket boosters. And remember that Star Trek communicator? Most people now carry a version in their pocket. So who is to say there will not be a real time machine in the future? Einstein’s theories suggest time is not the constant we predict it to be but is relative to the observer.

“You often learn more by being wrong for the right reasons than you do by being right for the wrong reasons.”

The integration of middle grade science fiction as a mainstream choice for readers is particularly important. It fills in a landscape of books primarily occupied by adults. Middle grade is an age where students are devouring literature but rigid dictums of what it takes to get into college are steering them elsewhere. Slightly more sophisticated than books for younger children but accessible across multiple age groups, MG sci-fi is now finding a broad audience. In those pages readers can follow imperfect, often not quite “ready for prime time” characters like themselves who stretch beyond their boundaries while still dealing with normal every day feelings and reactions to fantastical events. Kids (and adults) who make mistakes and learn resilience through failure. Characters who bicker but still come together at the right moments to combine their collective experiences to fashion out a solution to the ongoing struggle at hand. Science fiction can deal with race, conflicts, or just petty turf wars and bullies but in a way that hints at something bigger and better than our individual selves at the end.

And honestly, I’m encountering a number of adults now confessing they read MG Sci-fi because it can be thought provoking and fun. The conversations start with “I don’t usually read Middle Grade but I loved. . . “

Incorporating math and science, our genre opens up possibilities by tapping into a reader’s internal motivation to make things happen that don’t yet exist. It strips away barriers to asking “What if?” and translates the text into a roadmap for getting there, even if “there” is hundreds of years away.

Middle grade science fiction is where dreams live and hope flourishes. It is a glimpse at our future. It is a seed planted.

And so we write.

“The only thing that makes life possible is permanent, intolerable uncertainty; not knowing what comes next. ”

Christine Taylor-Butler is the author of more than 80 books for children, including her science fiction series: The Lost Tribes. A graduate of MIT, she has found her tribe among the geeks and nerds who see a future full of hopeful possibilities. She currently lives in Kansas City, MO with her husband, a tank of fish, and cats who consider her both servant and head of their pride. She is proud member of SteaMG, Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) and the Kansas City Science Fiction and Fantasy Society.

http://www.ChristineTaylorButler.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristineTaylorButler.ChildrensAuthor/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/christinetaylorbutler/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/ChristineTB